Free Acid Value vs pH in AHA Peels

Alpha hydroxy acid (AHA) peels have long been a cornerstone of both cosmetic and medical aesthetic practice. Glycolic, lactic and mandelic acids in particular are used to refine skin texture, improve radiance, manage mild acne and stimulate collagen production. Yet, the numbers on a product label often tell only part of the story. A peel that claims to be 20 per cent glycolic may act with strikingly different intensity depending on its formulation. The true determinant of effect is not simply the stated percentage but the relationship between concentration, pH and the resulting free acid value (FAV). This balance defines how much of the acid is biologically available to penetrate the skin and trigger exfoliation, and it is the single most important metric for predicting how a peel will behave in practice.

To understand why this matters, it is worth revisiting some chemistry. AHAs are weak acids that exist in two forms: ionised and unionised. Only the unionised or “free” molecules are sufficiently lipophilic to move across the stratum corneum and reach viable keratinocytes. The proportion of molecules in the free state is governed by the acid’s pKa, which is the pH at which half of the molecules are ionised. Glycolic acid, for example, has a pKa of around 3.83. If a peel is buffered to a pH close to this, about half the molecules will be free. If the pH is lowered below the pKa, the fraction of free acid increases steeply. A 10 per cent glycolic formula at pH 3.5 has an active free acid concentration of roughly 6 to 7 per cent. The same 10 per cent at pH 2.5 will deliver closer to 9 to 10 per cent, almost double the biological activity without any change in the headline percentage. At pH 4.5, by contrast, the free acid content drops to around 3 per cent, resulting in far gentler action.

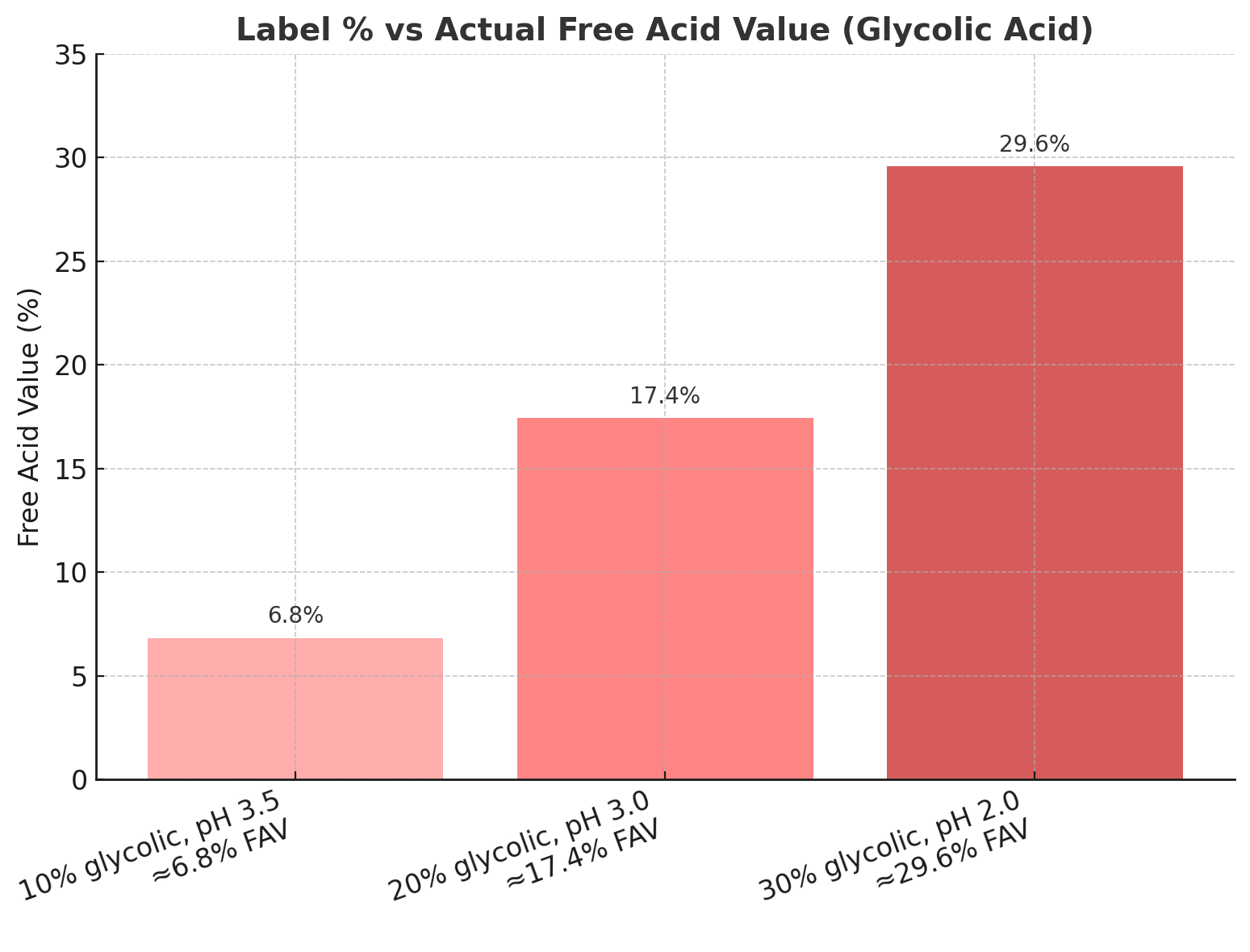

The logarithmic nature of pH explains why small changes have such large clinical implications. Each drop of one pH unit represents a tenfold increase in hydrogen ion concentration, which drives the equilibrium toward the free acid state. Two products that appear almost identical in concentration can therefore feel completely different on the skin. A 30 per cent glycolic peel at pH 2 may act with a free acid concentration approaching 29 per cent, producing rapid penetration and brisk epidermolysis. A 30 per cent peel buffered to pH 3.5 delivers less than half that amount in free form, offering controlled exfoliation and a markedly lower risk of post-inflammatory pigmentation or scarring.

This is why product labelling requires careful scrutiny. The three essential pieces of information are total concentration, pH and whether the formula is buffered. The term “buffered” means that a neutralising agent has been added to raise the pH, thereby reducing irritation while retaining the marketing appeal of a high percentage claim. In professional practice, a peel that states its concentration but omits pH is essentially uninterpretable. Responsible suppliers should provide full specifications, including independent testing of pH stability. Without this information, practitioners are unable to gauge the true clinical strength of the formulation and may risk either under-treating or, more concerningly, over-treating a client.

To illustrate how these variables translate into practice, consider a series of real-world examples. A 10 per cent glycolic solution at pH 3.5 behaves like a mild exfoliant, appropriate for home care or very sensitive skin. The free acid concentration is around 6.8 per cent, sufficient to smooth fine roughness and enhance hydration through its humectant effect. Increasing the concentration to 20 per cent and lowering the pH to 3.0 yields a free acid content of roughly 17 per cent. This is a true professional peel, likely to induce visible desquamation and significant improvement in pigmentation and photoageing. At the higher end, a 30 per cent glycolic at pH 2 contains almost its entire concentration in free form, approaching 29 per cent. This produces aggressive exfoliation that should only be performed by trained practitioners under controlled conditions, given the associated risks of erythema, blistering or post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Clinical decision-making must also take skin type into account. Fitzpatrick I and II clients may tolerate stronger formulations, but those with higher Fitzpatrick scores are at greater risk of pigmentary disturbance after aggressive exfoliation. For darker phototypes, buffered formulas or those with higher pH are often safer choices, achieving gradual improvements while preserving epidermal integrity. Equally, clients with a history of eczema, rosacea or barrier dysfunction should avoid high free acid values, as their skin is predisposed to irritation and compromised healing. The clinical sweet spot for most patients lies between 4 and 8 per cent free acid, sufficient to achieve cell turnover and collagen stimulation without tipping into excessive inflammation.

Safety protocols are therefore inseparable from chemical knowledge. Patch testing is essential when working with high FAV formulations, as is informed consent that explains not just the percentage but the interplay of pH and acid availability. Aftercare must be emphasised, with strict use of sunscreen, gentle cleansers and non-comedogenic emollients. Clients should also be educated about the difference between “stronger” and “better”. A peel with higher free acid content may deliver faster results, but it also carries greater risk, and outcomes are best when treatment is titrated to the individual’s skin type, concern and tolerance.

Ultimately, understanding free acid value allows professionals to bridge the gap between the marketing number on the label and the reality of clinical effect. Percentage alone is a blunt measure that often misleads, while pH provides the key to how much of that acid is actually active. When both are considered together, practitioners can predict peel behaviour with much greater accuracy and deliver treatments that are both effective and safe.